Taking On The Patriarchy - One painting at a time - Artist Jane Clatworthy

Based in London Jane was educated at the Heatherley School of Fine Art, London and has been tutored by artist's around the globe including, Caroline Jasper (Puerto Rico), Jeff Hein (Salt Lake City, Utah), Andrew James (Art Academy, London), Stuart Elliot (Artistic Anatomy -LARA).

Jane recently made an appearance on this year’s Sky Portrait Artist of the Year competition. We also had the pleasure of sitting down with the artist to chat about what she's up to. Read on to view her latest works and learn a little more about this exciting and controversial artist.

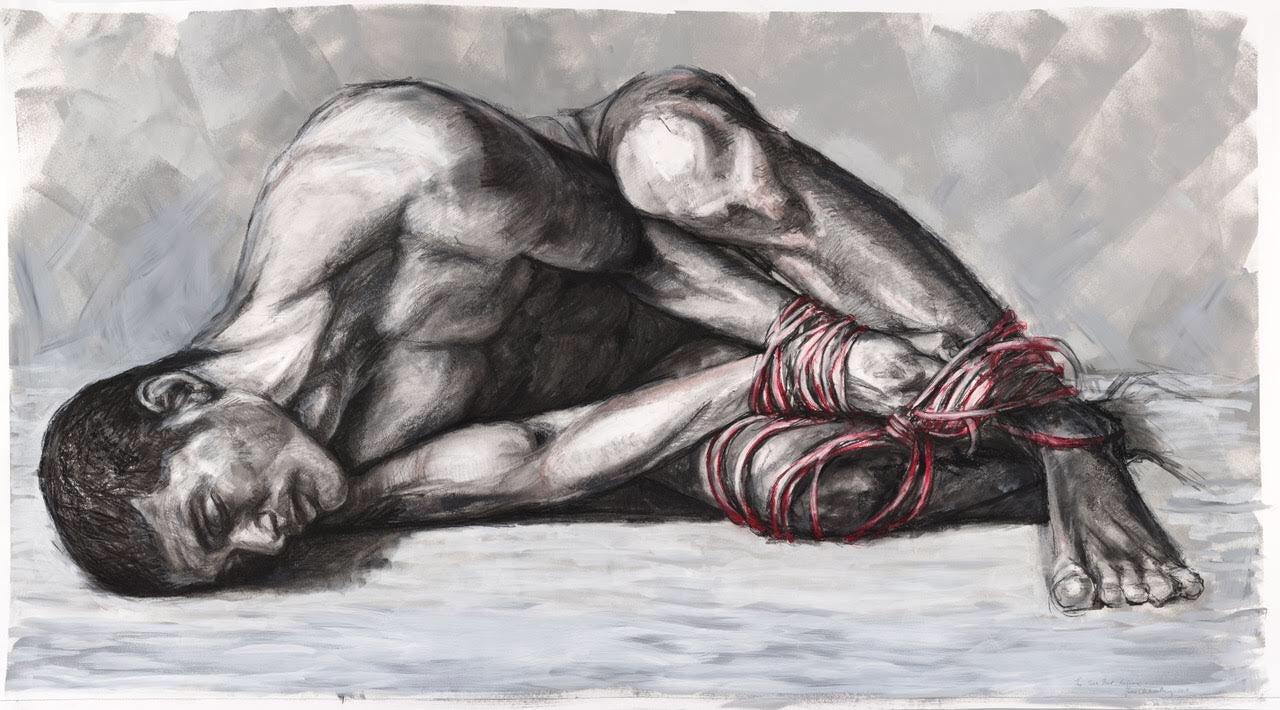

"On the most simplistic level, I feel compelled to address the imbalance we see across gallery walls. If men can paint women, why not the other way around? I’m seeking to demonstrate that a man can be a muse for a woman artist."

To purchase or commission Jane's work contact her using Ref: HATCH at jane@janeclatworthy.com and follow on Instagram @janec_art

H: Where does your interest in art come from?

JC: I can’t remember there ever being a time when I wasn’t interested in art. I honestly don’t believe it came from anywhere, it simply has always been with me. While the other kids were on the playground chasing a ball (or each other) around, I was somewhere drawing or reading, which is probably why I’m so rubbish at sports and was always the one last picked for the netball and rounders team (when I was forced to join the group activities). Yeah, I was that nerdy kid at the back, wishing like hell I could be doing something else.

H: Your first ever experience of ‘art’?

JC: I must have picked up a crayon as a pre-verbal child and just lost myself in drawing; creating imaginary worlds and superheroines, alongside magical fairies and dreamlike landscapes. Colouring-in books were never for me, I was always and still am, utterly enhanced by a blank sheet of paper and canvas. As soon as I could borrow books from my local library, they were always art related (with a few Enid Blyton’s thrown in too). The books were my introduction to the world of art and the artists that populate it; I remember being very in love with the Impressionists, especially Renoir and Degas, who I used to copy relentlessly. In the adult section of the library, there was an artistic anatomy book that I begged to be allowed to borrow, and once I did, I borrowed it repeatedly, copying the drawings over and over again. Human anatomy had me transfixed from the very start.

H: What inspires you?

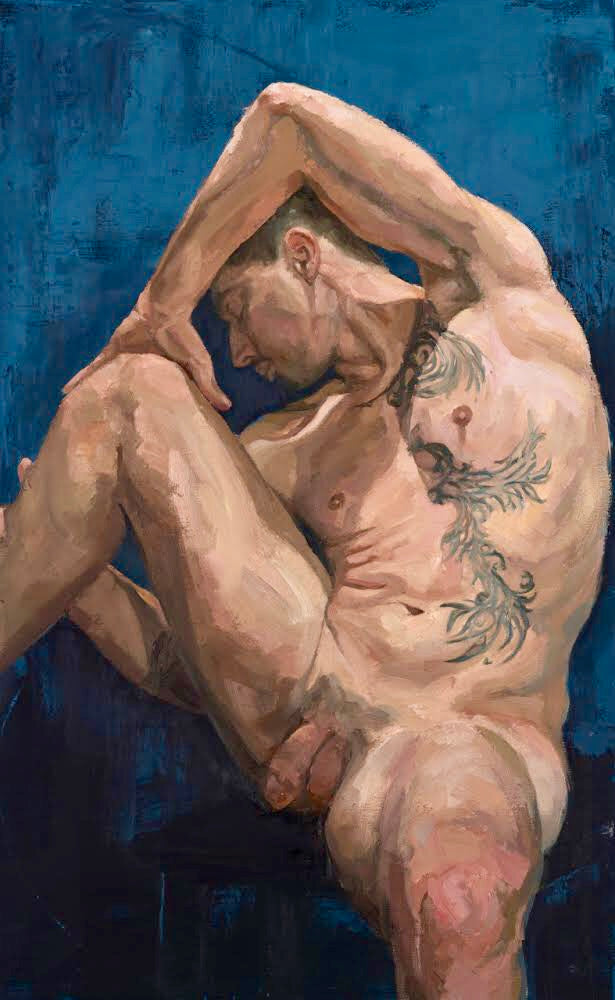

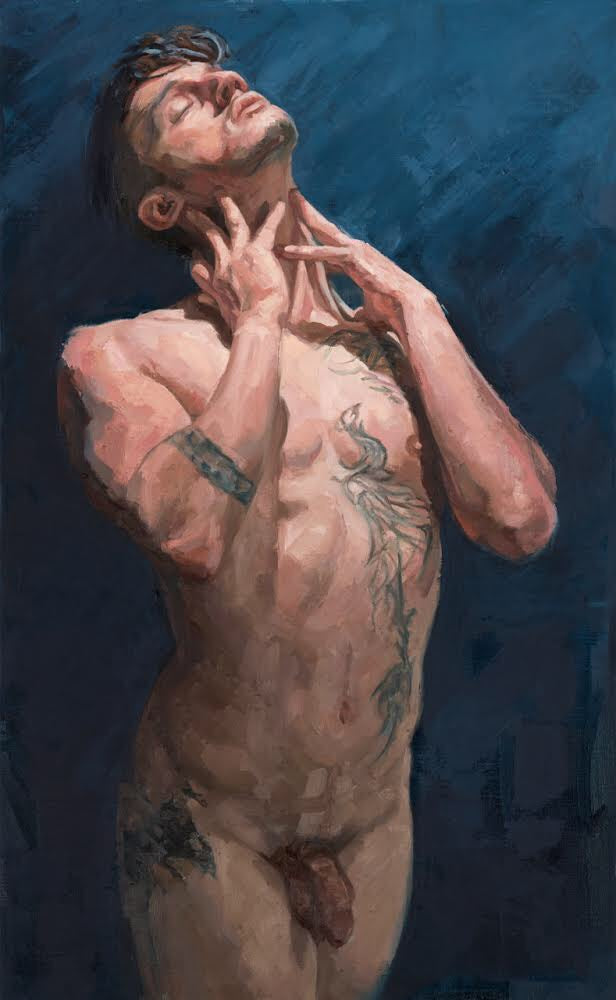

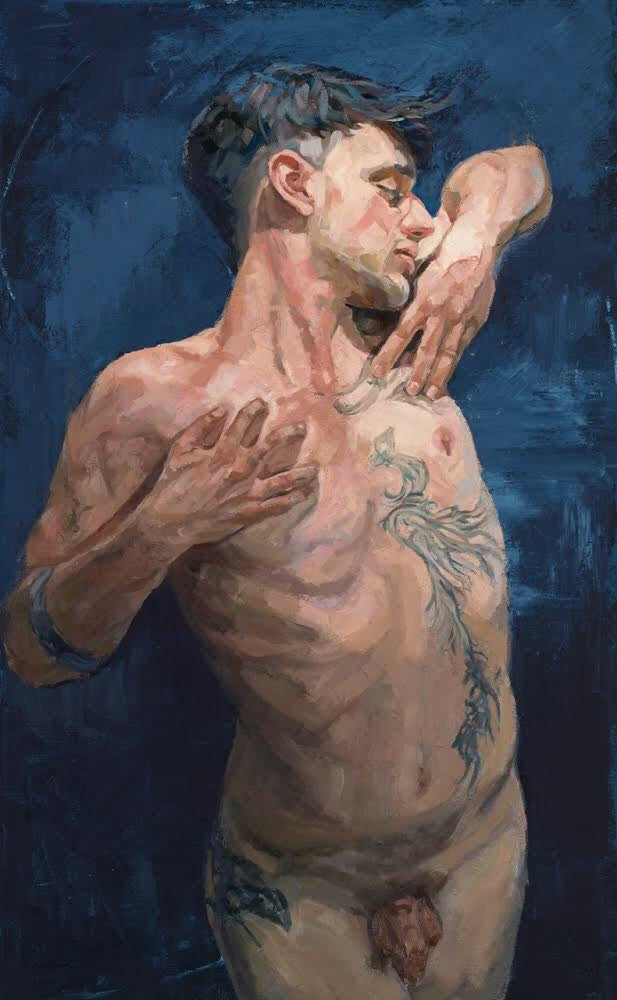

JC: Humans inspire me. Flesh inspires me. Emotions that are written across the body inspire me. Once all the protective armour of clothing is removed, and the human body, exposed and beautifully defenceless is in front of me, I start reaching for the poetry of life. We have learnt through all our social interactions to arrange our faces to please and to hide, to not show our deepest emotions, our vulnerability, our painful thoughts; the pathos and ecstasy of our existence. We mask ourselves, but our bodies reveal us, not just with naked flesh, but once nude, I see the verses written thereon, the experience of life that cannot be hidden. A muscle pulled tight, a languid motion, subtle storytelling in the way we hold ourselves. Even professional models can sometimes give away more than they mean to, especially if the artist is an acute observer of life. Also, the story written across the male body is one that has not been told enough, we have turned away, refused to see the entirety and beauty of the man, denied him the ability to be fully seen, and there are stories there that need to be told, balance needs to come back into ‘the gaze’, and to our existence together as we navigate this life.

H: Why the male nude? What does your work aim to say?

JC: There are multiple layers to the reason my focus falls so strongly, but not exclusively, on the nude male form.

On the most simplistic level, I feel compelled to address the imbalance we see across gallery walls. If men can paint women, why not the other way around? I’m seeking to demonstrate that a man too can be a muse for a woman artist.

The contemporary art world is currently making a concerted effort to address the number of female artists they represent; The institutions and museums are scouring their archives and collections to bring into the light more paintings done by women artists. I’m more interested in bringing male bodies, exposed, nude, naked and vulnerable into the mainstream public arena of those gallery walls.

I aim to disrupt ‘the gaze’ that falls so strongly on the female form, and I want to push strongly against the idea that the ‘beauty’ of the human form is the preserve only of the feminine.

I have set out to challenge and ask the viewer to question and explore their implicit bias against the male nude. Why is there such an apparent reluctance to embrace and explore the male body as part of the experience of being a female artist? Why do women themselves turn away in distaste from the idea of painting the entirety of the male form in a way that could be pleasing to her? Why do we look away? Her male counterpart felt no hesitation in this regard.

It can be argued that our culture is ‘so saturated with male bias’ presenting only a male view of cultural norms that women are kept from expressing and experiencing their own reality, one that might include men as objects of desire as equally exquisite and as pleasurable to paint as all the luscious female flesh that adorns those gallery walls.

From birth women are presented with a barrage of material designed to stimulate male sexual urges, nearly every form of media is complicit in this regard. What began in the Renaissance with lascivious depictions of the ideal woman, is continued today through nearly every channel with which women come into contact. That woman should ‘present’ herself for male pleasure is a constant message, seldom is there a reciprocal requirement.

Given these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that women turn their gaze, narcissistically upon themselves, suppressing and denying the same urges that have prompted male artists to lovingly depict their own muses throughout history.

Women have absorbed a heterosexual male centric view and the rhetoric that the male nude is less aesthetic, they have suppressed their own desire to look at the nude male body; generations of women artists protected by a metaphorical and psychological ‘posing pouch’, a learned reflex so inculcated that women today still don’t dare to look, suppressing the gaze that would be a powerful weapon in reintroducing balance between genders.

It’s a common presumption in society that women are not as visually stimulated as men and that women require a multi sensory stimulation for pleasure, hence the ‘male gaze’ explaining why most pornography is not aimed primarily at women. I would postulate that the ‘patriarchy’ has so thoroughly programmed women to look away and to suppress their own erotic desire, unless geared towards pleasing a man, that many women (artists) are disconnected from themselves and all the power of their own female gaze.

What ‘the patriarchy’ has sought to control is their own vulnerability. To be vulnerable is perceived as relinquishing power. Men know they are ‘weakened’ when confronted with the profound power of the sexually potent woman, one who dares to look back at him. If she could look from the man in front of her to the nude idealised man in the painting behind, I have no doubt he would feel his power diminished, just as surely as women over the aeons have so been when confronted by visions of themselves looking back out from the canvas with implicit adoration at the owner of, not just the painting, but by implication her too.

We live in a phallocentric culture, yet the concept of the ‘phallus’ as the centre of power is much diminished if separated from the physical reality of the penis itself. Take away the conceptual power and all you are left with is a very vulnerable piece of human anatomy.

‘If the penis has been hidden to protect it from the female gaze, it is partly because man is uncomfortably aware that, from his birth and infancy, through illness and death, woman, as a mother, lover, and nurse knows the male body in all conditions, from tiny penis to erect sexual organ to the limp bloodless appendage of the aged father’.

"This humanisation may however impair ‘patriarchal hegemony’ for once the penis becomes visible then the phallus becomes unveiled and its power undermined. Only once we start to fully embrace that there are no differences, that each gender is fully whole ‘can art attain the possibility of its own reintegration, reanimation, reincorporation, and de-castration’ (Quote from Wet: On Painting, Feminism, and Art Culture Excerpt from WET by Mira Schor

With my focus on the male nude, I am attempting a ‘humanisation’, a ‘reintegration’. I want to open up a space through art where men (and women) can see the male in a rare state of intact vulnerability and from there to start a broader conversation about the forgotten strength of a feminine that is no longer subservient to the masculine.

It is an axiomatic fact that men and boys are breaking down under the societal pressure to conform to the traditional traits of an idealised masculinity; that to be dominant, singleminded, self-reliant and stoic holds high value. To openly express the ‘less worthy’ feminine values of collaboration, connection, empathy, openness, nurturance, to desire emotional connection, would risk having their ‘maleness’ diminished and their man card revoked.

The outcome of being denied the full narrative and expression of our common humanity, the frustrations of being forced to conform to a singular ideal finds an outlet in the pervasive culture of ‘toxic masculinity’, a toxic masculinity that is a danger not only to women and girls, but to any human who does not conform to socially constructed gender norms.

It is simply not enough to attempt to address the profound problems of our current chaotic times by playing a gender numbers game within our public institutions and corporations; to enforce gender diversity in the public sphere is merely a form of biological essentialism, meaning it puts the full weight of responsibility for undoing the disfunction created by a few thousand years of a phallocentric, masculine dominated world on the shoulders of ‘not-men’; it implies that the traditionally masculine identifying male does not need to change. Women are oftentimes conflicted within themselves and struggle with the notion that masculine values are deemed of higher worth, necessary to embrace to be successful. The world does not need more women ‘beating the men at their own game’, proving they are just as capable of wielding all the weapons of masculinity as a man, it needs a new game with new rules. It needs equal players across the spectrum.

We need a world where the feminine is not defined in terms of lacking (a penis), but where feminine values are as equally powerful, desirable and revered as the masculine, we need a resurgence and revaluation of feminine power so all humans are free to express the full spectrum of the feminine and masculine within, only then will the gender wars be at an end.

Feminine values need to be re-empowered and resuscitated across all parts of culture and society so for my own small part as an artist and a woman, I am looking back, stepping into my own powerful gaze, returning the penis to its original humanity, not to objectify, not to diminish, but simply to love, to desire and to celebrate the beauty of a form that is not my own.

I invite the viewer to do the same.

H: Which current art world trends are you following?

JC: I tend not to follow any particular contemporary trend, I prefer rather to refer back to strong figurative artists who are particularly good at the language of the body and capturing fleeting moments of emotion. I’m aiming ambitiously for the work I do to endure beyond any ‘trend’.

H: Do you have a creative hero? & Who are your biggest influences?

JC: It goes, almost without saying, I must reference Jenny Saville, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, and not least of them, Rembrandt, and though considered an abstract artist, I’m a big fan of Cecily Brown. I can’t think of anyone who matches Rodin’s ability to capture the sensuality of the human body. I also admire greatly, female artists who pushed, are still pushing boundaries of what is acceptable to the current art world that, like it or not, still has a heterosexual white male bias; Betty Tompkins, Marilyn Minter, Mira Schor leap to mind.

H: Tell us about your process.

JC: My process most often starts with my own emotional state which inspires the content of the work and the direction it will take. Ideas for a painting often appear fully formed in my mind, the trick is then to backward engineer them to break apart the ‘why’ and then the ‘how’ of their existence. The practical side of the process starts with a drawing, a scaffolding upon which to hang the paint. I don’t really over plan anything, as I like to work things out on the canvas in a more spontaneous fashion unless a particular theme needs a more careful approach. When working directly from life, I’ll mostly just go straight to the canvas and roughly draw in paint - it’s a much more dynamic fight as the sitter always moves, but this makes for a livelier portrait as my brush follows the body’s position over the series of sittings. Inevitably, over the course of the project, the painting develops in emotional content as the artist and sitter get to know one another. When I working from a photo reference, I’m a little more exact in terms of form, but because I’m not interacting with another person in the room, I go deep into my own psyche as I paint - I probably reveal more of myself in these paintings as I unconsciously unmask myself. As for materials, I work with oil and sometimes cold wax as a medium. I love the texture that comes from the many mistakes so I very seldom scrape off something that is wrong, I’ll just work over it, laying down a record of the fight, giving the painting a history like strata in the landscape. I like my bodies to feel as though they are solid enough to caress and hold, so much so I often wonder if I’m not a frustrated sculptor. Music too is intrinsic to my process, and maddeningly I’m sure for my neighbours, I pretty much have the same playlist on repeat and it’s made up of both classical and contemporary work.

H: What would be your dream commission?

JC: Oh, when a man is confident enough to commission a naked portrait or purchase a painting and not feel diminished, threatened or condemned by society; to see the male nude as subject matter become as mainstream as the female nude.

H: How do you deal with creative block?

JC: Creative block is the holding space between ‘no longer’ and ‘not yet’. When a project is complete and the next one hasn’t yet presented itself, the trick is not to panic, but to honour the stillness. Fear will create a true ‘block’, but if you can trust yourself and your ability to create, if you can step into the space, embrace and reframe it as ‘quiet time’ rather than ‘block’, the ideas will eventually flow. I find too, just making a mark on paper, or painting anything at all, keeps the wheels oiled so to speak, ready for when the next idea has you racing along.

H: What are you working on next?

JC: Most of my work is centred on the male nude so at the moment an idea is percolating that explores the wisdom/pathos of middle age rather than the ecstasy of youth; taking inspiration from and referencing the old masters such as Ribera, Fortuny, Caravaggio, Michelangelo. To only focus on the beauty of youth would be to mirror the problem I see with the ‘male gaze’ in the zeitgeist; it looks away from and invalidates the beauty of the ageing (female) body.

H: Outside of art what makes you the happiest?

JC: At the risk of this answer appearing contrived rather than sincere, the honest truth is that there is no ‘outside of art’. I am not sure there can ever really be a life that isn’t so fully intertwined with my drive to create that there is any form of separation. The artist and the woman are one and the same so art is not something I go to a place to do - it simply is a part of everything I am. I can answer, that sitting in quiet contemplation and observing the grandeur of nature unfold around me, be it sea, forest or mountain, is a happy space (outside of the studio) to inhabit for a while. Failing that, I’m an avid reader of poetry so I often disappear there. Always though, the umbilical cord remains unsevered and once uncomfortably stretched, I am soon pulled back into the diving bell of my studio, perhaps a little replenished by the space and fresh air of these in-between moments.

H: How would your friends describe you?

JC: Instead of guessing, I simply asked them. The answers are from my FB page - I was both amused and deeply humbled as I received the best ego stroke ever. A compilation: “Nuts, independent, fun, no fucks left to give. Courageous, unstoppable, stubborn, intuitive and ‘feminine in a masculine way’. Honest, direct, always moving forward. Pioneering, on the brink of fame and fortune” - (which would be rather nice ;))

H: What one thing would you change in the world if you could?

JC: I’d erase the divide between the masculine and feminine. The disconnect between the two halves of ourselves is at the core of so much destruction and pain. This culture that sees men believing in an innate right to make decisions about the bodies of women(and girls) without their consent; from unwanted sexual advances; curtailing reproductive rights, devaluing their labour, contribution and worth; disempowerment at every level. I think the part of men that have been suppressed and denied; their need to be vulnerable, to be seen, to be acknowledged, to be desired, has been frustrated for so long, it has fuelled ‘the patriarchy’ which is most often expressed through the ‘toxic masculinity’ which harms all of humanity, and the planet too. We need to come back together to heal, to love and to become whole.

H: If you were to tag yourself on HATCH, what 3 words would you use?

JC: An artist friend of mine observed that I could ‘paint cock well’ which made me laugh out loud - so ‘paints cock well’ is probably a good answer to the question. To throw in three ‘polite’ words, I’d use ‘disrupting’, ‘challenging’, ‘outlier’.

H: Ok, last one......tell us a secret?

JC: I would if I had any of my own to tell. I speak my mind, I share (most likely over-share) my stories and my emotional state is probably writ large upon my canvases.

Jane Clatworthy

excellent – well done ….

Britta dwyer – retired art history lecturer with a focus upon gender studies

and the representation of the female figure in art (from renaissance to present)

you’ve given much food for thought! thanks

Very Proud of you Jane! You did it! Followed your inner whisper and gave life and substance to your inner stirring and imaginings . Stride onwards and upwards 💐🎨🌹

I know Jane Clatworthy only at a great distance, primarily Instagram, and primarily through her paintings. Now, through this article, I know her a bit through her words as well. In both she is articulate, honorable and admirable. Thank you for publishing this interview.